John Terence Kelly, Architect, 1922–2007

1968 CLEVELAND ARTS PRIZE FOR ARCHITECTURE

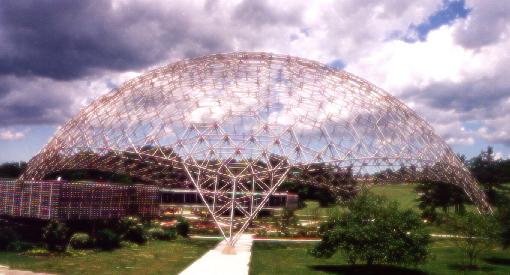

The enormous geodesic dome that

looms above the corporate headquarters of ASM International (formerly

the American Society for Metals) in Novelty, Ohio, 20 miles east of

Cleveland, has been turning heads along Route 87 for more than 50

years. The sheer boldness of its conception, realized in 1958 when

Eisenhower was in the White House, still causes jaws to drop and hearts

to leap. The effect deepens when one learns the 80-ton cobweb of

aluminum struts is suspended over a “garden” of rare metals gathered

from around the earth: an awesome example, its architect John Terence

Kelly liked to say, of what humankind has been able to do with those

materials—indeed, transcend gravity itself to create environments

suspended in space.

The enormous geodesic dome that

looms above the corporate headquarters of ASM International (formerly

the American Society for Metals) in Novelty, Ohio, 20 miles east of

Cleveland, has been turning heads along Route 87 for more than 50

years. The sheer boldness of its conception, realized in 1958 when

Eisenhower was in the White House, still causes jaws to drop and hearts

to leap. The effect deepens when one learns the 80-ton cobweb of

aluminum struts is suspended over a “garden” of rare metals gathered

from around the earth: an awesome example, its architect John Terence

Kelly liked to say, of what humankind has been able to do with those

materials—indeed, transcend gravity itself to create environments

suspended in space.

But this breath-taking structure contemplated from another perspective (inside looking out) may be equally moving. For the soaring latticework of the dome, which uses structural principles worked out by Buckminster Fuller, was inspired by Kelly’s memories of leaning back in the front porch swing as a young boy in Elyria, Ohio, and gazing up through the rose-trellis latticework at the sky beyond. Such boyhood experiences surely had something to do with the man’s conviction that an architect’s work involves recognition of the complex relationship that exists between a new presence and the natural (and other man-made) forms among which it finds itself.

As a young architect coming onto the scene in the early 1950s, Kelly was disturbed by the frantic building boom that followed World War II and its often undiscriminating lust for “the new.” What would come to be called the “throw away” culture. He deplored “the loss of so many invaluable structures” bulldozed to make room for soulless boxes, among which he included public and corporate buildings and public housing. Americans had lost an appreciation for quality, he lamented, and for the beautiful.

After a stint in the U.S. Army Kelly took a job in a steel mill to pay his way through Carnegie Institute of Technology (B.A. in Architecture, 1949) before pursing a master’s degree in his chosen profession at Harvard University (1951) under Walter Gropius followed by a second master’s in Landscape Architecture (1952), rare among architects, under Hideo Sashi. Named a Harvard Fellow in 1952, Kelly was awarded the University’s prestigious Charles Eliot Traveling Fellowship and, the following year, a Fulbright Grant in City Planning to Munich, Germany.

He was only 31 when his justly famed Porter house in East Liverpool, Ohio, designed around an enclosed garden, was chosen by Progressive Architecture magazine as “Best Home of the Year.” Kelly quickly became known as a gifted architect with fierce principles. And equally fierce opinions. No major building in Cleveland had been commissioned from local architects, he noted, since 1929, when the Van Sweringen brothers had brought in “fashionable easterners” to design the Terminal Tower, “that blown-up [version] of what had been successful in the work of Christopher Wren around 1700 in England.” This, not to mention the fact that locating the city’s main railroad terminal on Public Square instead of at the north end of the Mall undermined Daniel Burnham’s concept of a group of magnificent public buildings oriented toward the lake. What was more, it refocused the city around a New England-style village green and, together with the pseudo-Colonial look of the Vans’ Shaker Square, fatally reinforced Cleveland’s conservative identification with New England and the British Isles (“a snobbery based on nothing”). Cleveland deserved its own look, Kelly argued passionately. “We completely passed up the opportunity to have a city that is of our own time.” And this, he lamented, decades after Frank Lloyd Wright had shown the way.

Part of the problem, said Kelly, who had studied painting, sculpture and the history of civilization at the universities of Biarritz and Grenoble in France, was that the bosses of the new industrial revolution “don’t know beauty.” Yet among the corporate clients drawn to Kelly’s “organic architecture” (architecture that grows out of the forms of nature) were Richman Brothers, which commissioned a shopping center in Indianapolis; the Erie County Bank and its branch office in Vermilion, Ohio; the National Bank of Dover (Ohio); and the American Society for Metals. Notable commissions in the Cleveland area would eventually include buildings and gardens for the Holden Arboretum; Bratenahl Place; St. Mary’s Church in Hudson, Ohio; Cleveland’s Marion-Sterling School; and a number of award-winning private homes.

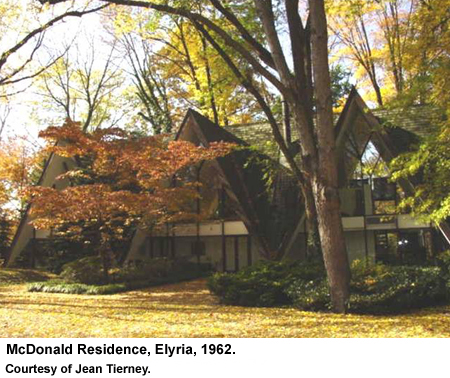

In 1962, Kelly’s McDonald House, in Gulf Farms, Elyria, was named one of the 20 best homes in the nation by Architectural Record. Featured in House and Garden magazine and Carol Ripkind’s A Field Guide to Contemporary American Architecture, its stunning design uses intersecting triple A-Frame construction, eight gables and a three-story expanse of glass supported by mullions of dark-stained wood that suggest branching trees. The open upper-floor plan, which overlooks this spacious, light-filled living area, allows an unobstructed view of the surrounding woodlands in several directions. Wright would have loved it.

—Dennis Dooley