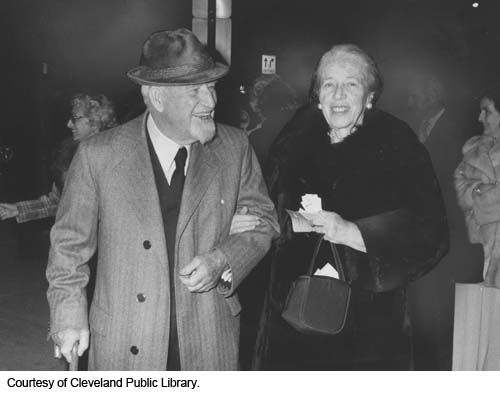

William M. Milliken,

The Armistice that ended the first World War was not a year old

when 2nd Lt. William Mathewson Milliken reported for his first day of

work at the Cleveland Museum of Art as its first curator of decorative

arts. Milliken, who had served with the U.S. Army’s 282nd Air

Squadron in 1917–18, was not yet

30. The museum had opened its doors for the first time just three

years earlier, in June 1916, and Frederic Allen Whiting, its first

director (1913-1930), was busy hanging art donated by several wealthy

Cleveland families, including the Allens, Holdens, Huntingtons,

Hurbutts, Nortons, Severances, Warners and Wades. Jephtha Wade, a

co-founder of Western Union, had also donated the property on which the

splendid neoclassic edifice of white Georgian marble now sat

overlooking Wade Lagoon.

The Armistice that ended the first World War was not a year old

when 2nd Lt. William Mathewson Milliken reported for his first day of

work at the Cleveland Museum of Art as its first curator of decorative

arts. Milliken, who had served with the U.S. Army’s 282nd Air

Squadron in 1917–18, was not yet

30. The museum had opened its doors for the first time just three

years earlier, in June 1916, and Frederic Allen Whiting, its first

director (1913-1930), was busy hanging art donated by several wealthy

Cleveland families, including the Allens, Holdens, Huntingtons,

Hurbutts, Nortons, Severances, Warners and Wades. Jephtha Wade, a

co-founder of Western Union, had also donated the property on which the

splendid neoclassic edifice of white Georgian marble now sat

overlooking Wade Lagoon.

Born in Stamford, Connecticut, in 1889, the son of Thomas Kennedy Milliken and Mary Spedding (Mathewson) Milliken, William had received a classical education at Stamford’s elite King School, Lawrence School in New Jersey and Princeton University (A.B., 1911). From 1913 to 1917 he had been assistant curator in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s department of decorative arts, where he’d spent many hours cataloguing the magnificent medieval collection donated by financier J. Pierpont Morgan Sr. This experience would later prove invaluable.

It was with the expectation that he would concentrate on modern art, however, that he had been brought to Cleveland; indeed, he was given the job of organizing the museum’s first May Show, the juried showcase for regional living artists introduced in 1919 that would become a beloved annual tradition for nearly seven decades. Milliken became a fierce champion of both the exhibition and the works of individual artists. (He would sidle up to a May Show goer whose attention had been caught by a particular work, relate interesting things about the artist and the work, and encourage its purchase it with the same ardor he used to persuade wealthy art patrons to buy pieces for the museum.) And, because of his own devotion to what many in the “serious” art world still dismissed as “decorative” arts, Milliken’s May Shows included a wide range of crafts, from gold- and silversmithing to ceramics—whose heightened visibility helped to build Cleveland’s reputation in those fields and launch several careers.

Meanwhile, through his astute recognition of superior work done by medieval craftsmen, the museum added a string of important acquisitions to its medieval collection, notably the Spitzer Cross (1923), the Bethune Casket and Gothic Table Fountain (1924), found buried in the gardens of a palace in Constantinople, the Stroganoff Ivory (1925), the Chalandon Enamel (1926) and, in 1930-31, the incomparable Guelph Treasure, nine exquisitely fashioned objects of gold, silver, enamel and precious stones, dating from the eighth to the 12th century and regarded as among the finest examples of medieval art.

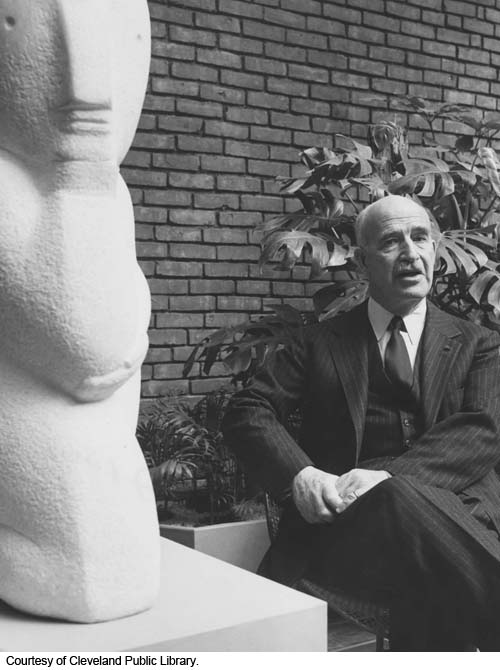

For although he had accepted the additional responsibility of curator of paintings in 1925, Milliken was adamant that a great museum—and Cleveland’s was going to become a great one—must collect the finest examples of every kind of art, without regard to current fashion. “Taste,” Milliken wrote in his 1977 autobiography, Born Under the Sign of Libra, “while partly instinctive, is also developed by familiarity and by basing one’s knowledge on great objects.” The Gertrudis Altar (c. 1040) is universally regarded as the greatest example of Romanesque art in America. The Stroganoff Ivory appears in every book on Byzantine art.

Thus—in addition to acquiring such renowned paintings as El Greco’s Holy Family, Tintoretto’s Madonna and Child, Toulouse-Lautrec’s Au Café, the American George Bellows’s iconic ringside image Stag at Sharkey’s,

and several 17th- century Italian masterpieces—Milliken also numbered,

among hundreds of acquisitions that established the Cleveland Museum of

Art as a world-class collection and his own reputation as one of the

great museum directors of the last century, stunning examples of

18th-century decorative art, as well as pre-Columbian and African art.

Thus—in addition to acquiring such renowned paintings as El Greco’s Holy Family, Tintoretto’s Madonna and Child, Toulouse-Lautrec’s Au Café, the American George Bellows’s iconic ringside image Stag at Sharkey’s,

and several 17th- century Italian masterpieces—Milliken also numbered,

among hundreds of acquisitions that established the Cleveland Museum of

Art as a world-class collection and his own reputation as one of the

great museum directors of the last century, stunning examples of

18th-century decorative art, as well as pre-Columbian and African art.

In 1933, Milliken defied the fierce anti-Roosevelt sentiments of his trustees to accept an appointment as a regional director of the Public Works of Art Project; he was to become a highly influential advisor to the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Art Project that gave work to many unemployed artists. From 1946 to 1949, Milliken was president of the Association of Art Museum Directors and, from 1953 to 1957, of the American Association of Museums. He served as first vice president (under Georges Salles, former director of the Louvre) of the International Council of Museums (1956–59) and the Academie Internationale de la Ceramique (1957–58). A fellow of London’s Royal Society of Arts and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, he received several honorary degrees, as well as awards from the Hungarian, Spanish, Swedish, German, Italian and French governments for his generosity in lending important objects from Cleveland’s collection.

From the start Milliken had actively reached out to his own community, a policy that saw attendance records of 80,000 set for three weeks in 1931 and 375,215 for the year. One of the first directors to realize that museums must be more than repositories of important objects, he professionalized his institution's education department and worked with both suburban and city schools and nearby Western Reserve University (WRU) to greatly expand the museum’s services not only to children but also to adults. With funding from the Carnegie Corporation, he hired Thomas Munro to head the new department and secured Munro’s appointment as professor of aesthetics in WRU’s graduate school. Milliken also arranged for a member of the museum’s staff to give courses in WRU’s Flora Stone Mather College for Women. Builder of the museum's library, he was gratified to learn that, by 1932, 168,169 projection “lantern” slides (of 28,214 objects) were in popular circulation.

Sherman E. Lee, who succeeded Milliken as director, called him “a courageous and pioneering spirit” who “put the Cleveland Museum of Art in the mainstream of American cultural life. His enthusiasm,” added Lee, “was infectious, and his self-discipline and devotion set a high standard of professionalism.” Milliken’s tenure had seen the establishment of the museum’s Junior Council, the Print Club, the Textile Arts Club and the Musart Society, which supported the activities of a new department of music. Milliken personally pruned the trees in the museum’s Fine Arts Garden, rode horses for relaxation and attended baseball games incognito (he sat in the bleachers).

Writing shortly before Milliken’s retirement at 69 in 1958, the Plain Dealer’s Larry Hawkins described him as “a stocky, hard-muscled man. He got that way by working summers as a cowhand in Wyoming (in his earlier years),” said Hawkins, “by skiing at Sun Valley (every year) and by walking 21 times around the Fine Arts pond every day.” The elderly art historian did not own a radio or a TV set.

In the years that followed, Milliken, who had never married, would travel to Melbourne, Australia, to lend his insights to the planning of its new National Gallery; undertake a 20-lecture tour of Canada; make annual trips to Europe; and serve as the principal architect of the great Masterpieces of Art exhibition at the 1961–62 Seattle World’s Fair. Also named a Regent Professor at the University of California at Berkeley in his retirement years, he died in 1978 at the age of 88.

—Dennis Dooley