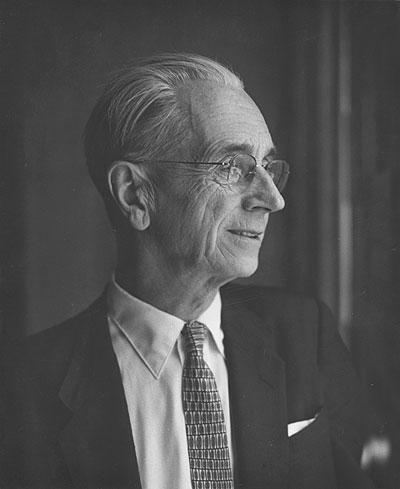

J. Byers Hays,FAIA, Architect, 1891–1968

1962 CLEVELAND ARTS PRIZE FOR ARCHITECTURE

Of all the architects active in Cleveland in the early 1960s, it was J. Byers Hays who was singled out for

recognition with the first Cleveland Arts Prize awarded in that

discipline. As he approached the end of his 43-year career (1920–1963),

Hays’s legacy to the area was everywhere to be seen.

Of all the architects active in Cleveland in the early 1960s, it was J. Byers Hays who was singled out for

recognition with the first Cleveland Arts Prize awarded in that

discipline. As he approached the end of his 43-year career (1920–1963),

Hays’s legacy to the area was everywhere to be seen.

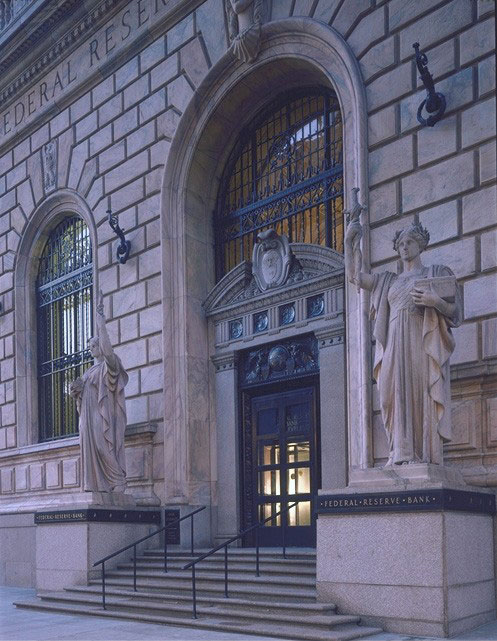

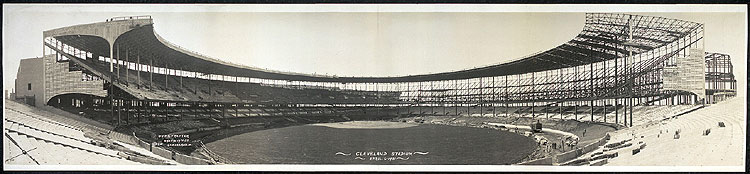

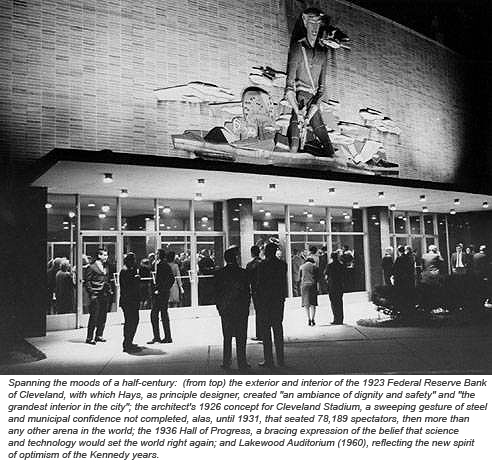

As principal designer with the firm of Walker & Weeks in the 1920s, he had given the city its stunning Federal Reserve Bank Building (1923), the proud exterior of Cleveland Municipal Stadium (1926), and St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Cleveland Heights (begun in 1927). As a principal in his own firms during the decades that followed, he created the master plan for the Cleveland Zoo (1948) and designed the bird and pachyderm houses, Lakewood High School auditorium (1960) and the first major addition to the 1916 Cleveland Museum of Art.

One is immediately struck by his ability to embrace, and produce exemplary work in, a wide range of styles. At 32, Hays was capable of creating what architectural historian Mary-Peale Schofield, writing half a century later in her respected study Landmark Architecture of Cleveland, would eulogize as “the epitome of the classical trend in banking architecture.” With “the glowing color of the Convent Sienna marble from Tennessee, the rich colors of the coffered, vaulted ceiling, and the delicacy and draftsmanship of the Swedish iron grillework” of the Federal Reserve Bank’s spacious inside, Hays had created, she said, “the grandest interior in the city”—while the early Italian Renaissance character of the building’s exterior, with Henry Herring’s symbolic sculptures and a massive pedimented gateway, established an ambiance of “dignity and safety.”

It was, however, as a proponent of the new International Style that Hays became chiefly known and revered. Born in Sewickley, Pennsylvania, in 1891 and graduating in architecture from the Carnegie Institute of Technology in 1914, he had just begun his career as a draftsman with the New York office of Raymond Hood when America declared war on Germany. By the time the aspiring architect accepted a position with Walker & Weeks in Cleveland in 1920, artists and architects in a shell-shocked, war-ravaged Europe were already saying good riddance to a civilization that had led to so much pointless carnage.

Having

contempt for all things Victorian and its reverence for the past, the

new modernist gospel embraced the impatient, built-for-speed character

of 20th-century life—with its radios, airplanes and (now) talking

pictures and jazz. In architecture, writes Eric Johannesen, “complexity

and picturesqueness were replaced by simplicity and severity; texture,

color and ornament by smoothness and plainness,” and the feel of

monumental solidity by transparency and deliberately exposed structure:

a celebration of the belief that science and technology would set the

world right.

Having

contempt for all things Victorian and its reverence for the past, the

new modernist gospel embraced the impatient, built-for-speed character

of 20th-century life—with its radios, airplanes and (now) talking

pictures and jazz. In architecture, writes Eric Johannesen, “complexity

and picturesqueness were replaced by simplicity and severity; texture,

color and ornament by smoothness and plainness,” and the feel of

monumental solidity by transparency and deliberately exposed structure:

a celebration of the belief that science and technology would set the

world right.

This optimistic new spirit is seen in Hays’s design (with his partner Russell Simpson) for the Hall of Progress at Cleveland’s 1936 Great Lakes Exposition, which featured a unique new system of visible wooden trusses; Lakewood High School auditorium (1960); and the Riverview public housing complex (1963). In their conviction that a rational approach to architecture was the way of the future for a rational society, Hays and Simpson (who had jumped ship together from Walker & Weeks after the Crash in ’29) created a prototype for a small modular home designed for family living that was actually constructed on GE’s Nela Park campus—as a response to the Depression economy. During World War II, Hays designed several war housing projects, and after the war, the Great Indiana War Memorial in Indianapolis.

Some of his most important work no longer exists. Some, like his zoo buildings and forward-looking Riverview apartments, has been modified or renovated by later architects to accommodate changing needs. His sensible, warmly functional addition to the art museum—which included an interior sculpture garden hidden from view by Marcel Breuer’s brutalist 1971 addition—has now been completely subsumed by the massive re-working of Rafael Vinoly. Hays’s contributions to Cleveland architecture nevertheless deserve a place in history. As much as any other figure, he embodied the city’s transition from the grand style of Daniel Burnham and the dignified Group Plan for Cleveland’s public buildings to a more modern idiom that responded to changing times and a new urban spirit.

J. Byers Hays, who died in 1968, lit the way for new aesthetic sensibilities and helped to shape what he and others hoped would be Cleveland’s new image of itself as an energized, forward-thinking urban center open to new ideas and new impulses. The statue he placed by the gateway to the Federal Reserve Building on Superior Avenue was a message to posterity. It is titled Energy.

—Dennis Dooley