Edris Eckhardt, Pioneer in Glass Sculpture, 1905–1998 1971 SPECIAL CITATION FOR DISTINGUISHED SERVICE TO THE ARTS

But Eckhardt, a contemporary (and colleague) of famed Cleveland artist and industrial designer Victor Schreckengost, was long neglected by art historians in an era when women artists were not taken as seriously as their male counterparts. “At the Cleveland School of Art (CSA) she was passed over for the Herman N. Matzen Award in favor of a male student,” remembers collector and friend of her later years, Joe Kisvardai, “because the committee felt the year of study abroad would be wasted on a woman who might choose family over career.” So, upon graduation from CSA (now the Cleveland Institute of Art) in 1931, Edythe Aline Eckhardt changed her first name to the more gender-ambiguous Edris. Born in Cleveland in 1905, the daughter of Rachael and Herman W. Eckhardt, a plumber who taught her to melt lead and solder joints, Edythe made up her mind early that she would not be held back by the silly rules of polite society. When she decided, at age 22, to enroll at the Cleveland School of Art, she simply lied and said she was 17 and just out of high school, same as all the other kids. There she studied painting with Frank N. Wilcox and William Eastman and sculpture with Alexander Blazys. By 1932 Eckhardt was in New York studying with—and working alongside—the famed sculptor Alexander Archipenko. By 1934, her own work was gaining such respect that she was offered a faculty job at CSA; and the following year, she was asked to serve as regional supervisor of sculpture for the Federal Arts Project, a program of the Works Progress Administration (WPA) that paid local artists to create murals, sculptures and ceramics on American themes. She held this position until the program ended in 1941.

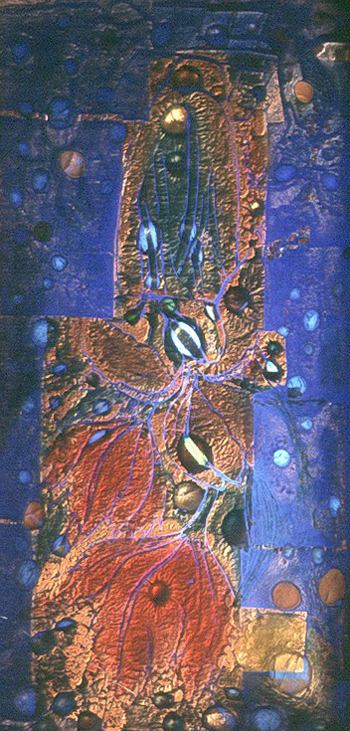

Many of Eckhardt’s storybook sculptures and other pieces for which she is justly famed were made using a process known as paté de verre (paste of glass) in which the separate pieces of glass are first cut and carefully assembled (“laid up”), then placed in a kiln. There, at lower temperatures than are used in glass blowing, the pieces take on the consistency of honey and fuse, after which the piece has to be slowly and very carefully cooled. Developed in Mesopotamia in the second millennium BCE and perfected by the Greeks and Romans, this “warm glass” technique had been lost for centuries before European craftsmen rediscovered it in the late 19th century and refined in the early years of the 20th. At the time Eckhardt was creating these pieces, says New Bedford Glass Museum director Kirk J. Nelson, only a few artists anywhere were using this complicated, disaster-prone technique. The iridescent quality of pate de verre, which seems to glow with an internal fire, would soon lure many others. In the 1950s Eckhardt, after thousands of failed attempts, rediscovered a process that had eluded her fellow artists for 2,000 years: the Egyptian art of fusing gold leaf between sheets of glass to produce gold glass, which resulted in some of her most powerful work. She was awarded two Guggenheim fellowships and a Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation Fellowship and was invited to teach at the University of California at Berkeley. In 1973, Dennis Barrie conducted an extensive interview with her for the Archives of American Art, which also houses Eckhardt’s papers (1927–1980). The Cleveland Museum of Art owns 12 of her pieces. For more on the artist, see Joe Kisvardai, “Getting to Know Edris Eckhardt,” Journal of American Art Pottery Association, July/August 2007. Eckhardt’s pieces still turn up for sale on gallery websites. —Dennis Dooley

|

Cleveland Arts Prize

P.O. Box 21126 • Cleveland, OH 44121 • 440-523-9889 • info@clevelandartsprize.org

The magical dimension

The magical dimension  It

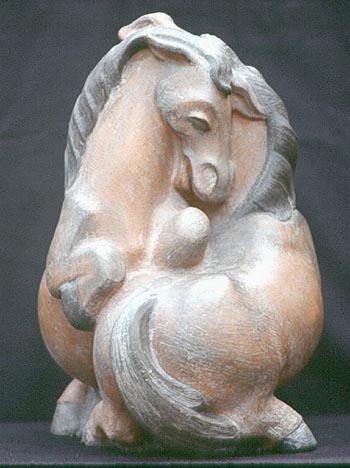

was through a precursor program that had lasted less than a year

(1933–34), the short-lived Public Works of Art Project (PWAP), however,

that Eckhardt got an opportunity that would have an enormous impact on

her career: creating sculpted figures from children’s literature for

display in public libraries across the U.S. Before long Marshall

Field’s and Neiman Marcus department stores would be selling her

creations. But these were no kitsch figurines. Art critic Douglas Max

Utter, reviewing a 2006 retrospective of Eckhardt’s work at the

Cleveland Artists Foundation at the Beck Center for the Arts,

co-curated by Kisvardai and the Cleveland Museum of Art curator Henry

Adams, finds “a sense of mystery” in them that is “captivating.”

Eckhardt’s huddled, highly detailed groupings of such legendary figures

as Alice, the Mad Hatter, Mock Turtle, White Rabbit and the scowling

Queen of Hearts—based on Sir John Tenniel’s original (now iconic)

illustrations—seem “like fragments of a lost world,” says Utter, “toys

in the attic of our culture.”

It

was through a precursor program that had lasted less than a year

(1933–34), the short-lived Public Works of Art Project (PWAP), however,

that Eckhardt got an opportunity that would have an enormous impact on

her career: creating sculpted figures from children’s literature for

display in public libraries across the U.S. Before long Marshall

Field’s and Neiman Marcus department stores would be selling her

creations. But these were no kitsch figurines. Art critic Douglas Max

Utter, reviewing a 2006 retrospective of Eckhardt’s work at the

Cleveland Artists Foundation at the Beck Center for the Arts,

co-curated by Kisvardai and the Cleveland Museum of Art curator Henry

Adams, finds “a sense of mystery” in them that is “captivating.”

Eckhardt’s huddled, highly detailed groupings of such legendary figures

as Alice, the Mad Hatter, Mock Turtle, White Rabbit and the scowling

Queen of Hearts—based on Sir John Tenniel’s original (now iconic)

illustrations—seem “like fragments of a lost world,” says Utter, “toys

in the attic of our culture.”